An insider’s view of the Australian wine industry and the Jacob’s Creek brand

Transcription of an interview with Phil Laffer, Canberra, 16 March 2006

Jacob’s Creek people

The winemakers

If you’re going to be a good winemaker you have to be passionate about it. And that means passion about wine, food, people vines and a whole range of other things.

It strikes me that the people who’ve built Jacob’s Creek – people like Stephen Couche who’s been the marketing person responsible for Jacob’s Creek for about thirty years. He’s managed Jacob’s Creek from a brand viewpoint all the way through.

Obviously there have been people working with him. But I think one of the strengths of Jacob’s Creek has been not just the disciplined approach to winemaking but an equally disciplined approach to marketing.

There’s not been a change to labels or a change to philosophy over time. While there have been lots of people contributing to Jacob’s Creek in a marketing sense. But you’ve always had Stephen sitting there guiding the process and, when necessary, applying the breaks, saying, “Look it’s a great idea but that really isn’t Jacob’s Creek”.

One only has to look at thirty years of labels for Jacob’s Creek to see that, yes, there’s been an enormous evolution. But it’s always been a managed evolution. There have been no enormous, radical steps.

Where we are today to where we started is quite different, but all along the way it’s been managed quite carefully. So, Stephen’s [Stephen Couche] 30 years is probably the most significant contribution to Jacob’s Creek.

From a winemaking viewpoint, we have people like Mark Tummel who was with Orlando for 40 years and was the initial winemaker for Jacob’s Creek.

Along the way he passed the baton to Robin Day who enjoyed 20 years’ service.

And Robin passed the responsibility onto me in 1992/1993. I see myself very much as the custodian of Jacob’s Creek for my period at Orlando. And I’m in the process of having successfully developed two very good people to take over from me – in the immediate future, Bernard Hickin and one to follow Bernie, Sam Kurtz.

Bernard and Sam are not just remarkably good winemakers, but also remarkably good people. They’re people who think outwardly. They’re people who are passionate about people, good communicators and are looking to encompass everybody into to Jacob’s Creek. And that’s very important.

It would be wrong to I think to have an enormous change of style in the person, in a wine sense, who would be responsible for Jacob’s Creek. That would, perhaps, lead to a change that may or may not be good. So there’s lots and lots of depth there.

Bernard has just celebrated his 25th anniversary with the company – so he’s been there ten years longer than I have – and Sam Kurz has just celebrated 15 years.

Bernard served with both Mark Tummel and Robin Day before working with me, meaning he’s worked with three people responsible for Jacob’s Creek winemaking – and he’s about to take it over.

All of that helps to explain the success of Jacob’s Creek

There’s been this great durability of people within Orlando, and particularly amongst those who’ve been associated with Jacob’s Creek. This guarantees a seamless move from one to the other.

Now that’s not to say that Bernard in his period as stewardship won’t make a whole lot of changes. If the market changes or consumers change then it’s going to be his job to be in tune with that.

But he’s seen how it’s progressed over 25 years, so he’s not likely to be someone to hop in say, well, they’ve got it all wrong, let’s do it differently. He’s had this association for 25 years and a very active involvement for at least the last 12 years.

He’s been responsible for all the white wine and sparkling wine in Jacob’s Creek in the same way that Sam has been responsible for the red wines. And that continuity and that ability to get the soul and personality of Jacob’s Creek is very important.

The grape growers, viticulturists and regions behind Jacob’s Creek

When I look at the long list of names of people who grow grapes for Jacob’s Creek, I realise that they’re not only long term growers, but characters in their own right and a big part of Jacob’s Creek.

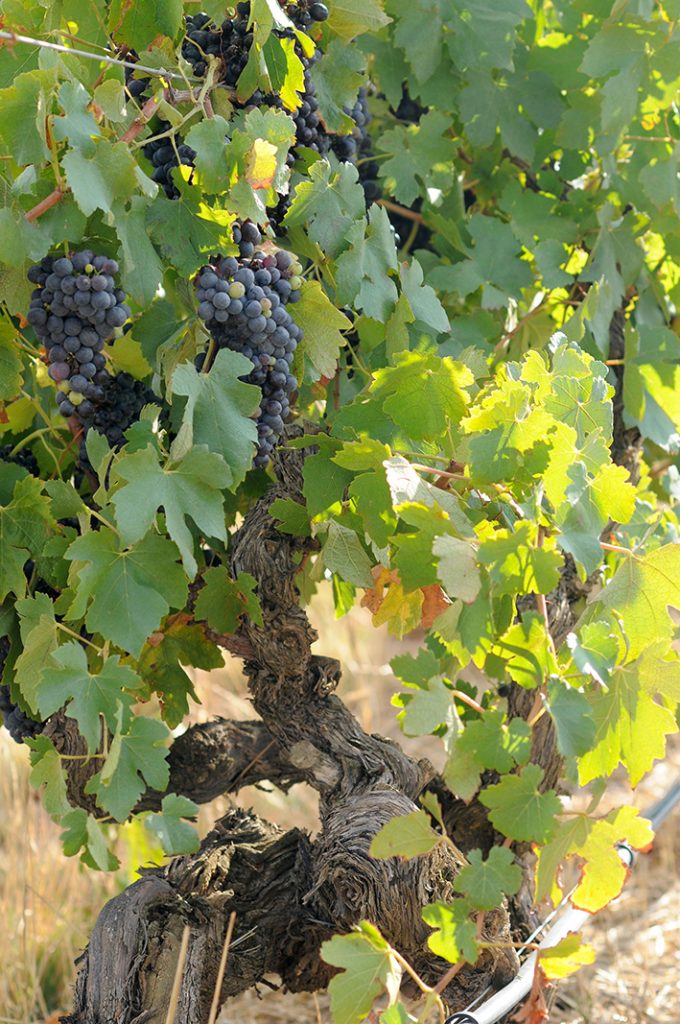

It’s interesting to look at the names. Koch, Neldner, Lindner,

Makner, Jenke, Schilde, Hofner, Gazanski and so on. They’re obviously German names in the main. So these are people who probably arrived in the Barossa about the same time that Johann Gramp did.

And they, as the Gramp family does, remain an important part of the Barossa Valley. I don’t know how long any of these have been delivering fruit to us. But I know that in the case of the Koch family it’s over one hundred years.

In the case of the Lindner family, we had a function four years ago with Cliff Lindner, who’s now seventy, and the function was celebrating when his father started delivering fruit to us. So it’s probably something like an eighty year association with lots of these people.

And they are part of the Jacob’s Creek family. Obviously Jacob’s Creek’s such a big brand now that it doesn’t all come from these old families. But they remain an important part of some of the wines. And they’re an important part of the tradition of Jacob’s Creek.

It’s not something that someone has developed out of blue sky. There’s this history of people and tradition that goes back to when Johann Gramp founded his company 155 years ago and when William Jacob named the Creek at about the same time.

In other wine regions, too, growers have long associations with Orlando and Jacob’s Creek – McLaren Vale for example and the South Australian Riverland.

Orlando has been sourcing fruit from that part of the world since the 1920s – initially from the soldier settler farms established after World War I. We still have something like a hundred growers in the area. Many of these – either they or their families have been delivering fruit to Orlando for over 50 years.

In other areas that association is not quite so long. The Orlando connection with the Riverina, New South Wales, started with a man called Charlie Morris, who built a winery in Griffith in the 1960s which shortly thereafter became part of the Orland family.

And from the 1970s onwards, the Riverina has been an important source of grapes for Jacob’s Creek and there has been an association with growers in that part of the world going back over 35 years.

The links there don’t go back quite as far as those with the South Australian Riverland, but they are just as strong. It’s a different background of grower.

In the South Australia Riverland they generally soldier settlers, where in the Riverina they tended to be Italian who’d settled there, having emigrated to Australia post Second World War.

Sunraysia, on the Victorian section of the Murray River, is far more recent. While we have been relying on Sunraysia/Mildura area for a number of years, it’s only been in the last five years that we’ve begun to build up direct and serious relationships with the growers.

But we’ve adopted the relationship and the philosophy – and there’s evidence already that these growers are enjoying and responding to our approach to the winemaker and grape grower relationship. We have substantially improved the quality of fruit – and hence wine – that we’re getting out of the part of the world.

We have growers in lots and lots of other areas, but they are the major ones.

In the last ten years or so we’ve developed quite a strong relationship with Clare, particularly with riesling but to a lesser extent with shiraz, cabernet sauvignon and merlot. We would now be, I imagine, probably the second or third largest purchaser of high quality out of the Clare Region – predominantly for Jacob’s Creek products.

Langhorne Creek is one of our biggest – if not our biggest – premium grape growing areas. For a long time we had relationships with a number of small to medium sized growers.

About ten years ago we decided it was a very exciting area and one way to increase our presence there was to establish what we thought would be a world-class vineyard there. That we did, with a view to providing us with very good fruit; to provide us with the opportunity to do an awful lot of experimentation as the vineyard was big enough to do that; and hopefully to provide some guidance to what was becoming an increasingly large viticultural region.

We are close to a stage where we will be drawing about 20 thousand tonnes of fruit from Langhorne Creek – which is not so far from fifty per cent of what is produced there. So it’s a very important area.

Our own vineyard is not as important today as it was when we developed it because Langhorne Creek has come of age. There’s now a critical mass of grape growers. And with that has come a lot more knowledge and a lot more infrastructure.

It’s a very good area because it tends to have a very low disease regime. It’s dry, therefore you can, to some degree, manipulate the viticulture by sensible and clever use of water.

And because of the natural air conditioning as the night breezes blow across Lake Alexandrina, evaporating water, and bringing night time temperatures down to ten degrees – despite the fact that day time temperature may have been as high as forty. This, of course, creates elegance in the fruit flavour.

And it’s close to home – about an hour by car or two hours’ by truck. As a consequence, we process the fruit locally.

The outstanding variety in Langhorne Creek is chardonnay. After that it’s shiraz and cabernet sauvignon, and merlot does well there, too. When you think about what Australia sells, it’s a great area.

The Limestone Coast zone is very important to Jacob’s Creek, though in volume terms it’s not as big as Langhorne. Stylistically it’s possibly more important.

We focus on three regions on the Limestone Coast: our greatest involvement is at Padthaway – where Jacob’s Creek has had an involvement for over 25 years. In the last 17 years we’ve drawn heavily on our own two vineyards there.

These produce, without doubt, our best chardonnay and some of the bests shiraz that Australia produces. It is not Barossa shiraz. It is not McLaren Vale shiraz. It’s a style of shiraz which is different. It suits Jacob’s Creek because there’s some elegance to it and it is without doubt the backbone to Jacob’s Creek Reserve Shiraz and plays an important part, albeit not in great volumes, in Jacob’s Creek Shiraz and Jacob’s Creek Shiraz Cabernet.

We source quite a bit of sauvignon blanc that supports JC Reserve Sauvignon Blanc. We’re now producing some very attractive merlot – for a JC Reserve Merlot due for release in October, 2006.

One hundred kilometres South of Padthaway, in Coonawarra, we have four distinct vineyards, all of them on the original cigar-shaped terra rossa soils. We have a number of long-term contract growers – in some cases with 20 year relationships.

Our focus nowadays is very much on cabernet sauvignon. Coonawarra is the sole source of Jacob’s Creek St Hugo Cabernet Sauvignon. It produces the base component for JC Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon. And the very best Coonawarra cabernet forms a key component of Johann – the icon wine of Jacob’s Creek.

Abutting Coonawarra in the south and Padthaway in the north of the Limestone Coast region there’s an emerging region called Wrattonbully, producing some very exciting wines.

What impresses us most of all is the quality and purity of the chardonnay. And it looks like Wrattonbully will also be producing some very, very fine shiraz – much in the style that suits Jacob’s Creek, with lots of flavour and a degree of elegance to it.

Our interest in NSW in volume terms is primarily the Riverina. But in terms of the style component in Jacob’s Creek, Cowra and Canowindra have turned out to be – and they are both relatively new grape growing regions – in producing a very peachy style of chardonnay which has enormous citrus elegance to it.

Now on their own, they’re one dimensional wines, but in a blend they are absolutely fantastic. And we contracting something like four to five thousand tonnes from this part of cental New South Wales because it fits remarkably well with this concept of elegance in Jacob’s Creek. It’s a nice counter to some of the rich wines that we get from South Australia and Sunraysia.

Further north in Mudgee we have our own vineyards and some very large contract growers. What appeals to us most there is the quality of the semillon which is very important for Jacob’s Creek Semillon Chardonnay and Jacob’s Creek Semillon Sauvignon Blanc.

The red wines of Mudgee are stylistically different from anything else in Australia. They have lots of up front flavour and then what people describe as a cliff – they come to an end. So, in their own right – and this is a classic case of where blending works – put them into a blend and they contribute some quite fantastic flavours. Now you don’t need a lot and we don’t have a lot. But a small bit of Mudgee is also key to this complexity we’re looking for in the Jacob’s Creek red wines.

From the Yarra Valley, Victoria, we draw sauvignon blanc as well as pinot noir for both red wine and sparkling wine.

From Tasmania we take chardonnay and pinot noir for sparkling wine. This material is key to the Jacob’s Creek Reserve Sparkling wine,

We take a small amount of chardonnay from Kangaroo Island – a unique small island where the climate is driven by the ocean temperature. It never gets extremely hot and it never gets extremely cold.

It’s a new grape growing area but it looks like, as a small player, an interesting component to some top end Jacob’s Creek chardonnays.

Interestingly, Kangaroo Island served as a staging point for early immigrants to South Australia. Johann Gramp landed there at a place called Reeves Point – now the name of Jacob’s Creek’s top chardonnay – and remained for several months before moving to the Barossa.

When Gramp landed there his group planted a mulberry tree from a cutting brought from Bavaria. That tree remains there. Cuttings from that tree were taken by Gramp to the Barossa and we have planted by Jacob’s Creek a substantial mulberry tree which is an offshoot of that original planting.

In Western Australia we have no winemaking facilities but we have relationships with two or three winemakers in whom we have a great deal of confidence to produce for us suvignon blanc juice which we then bring to South Australia for fermentation under our control.

We also take some semillon, riesling, chardonnay, cabernet sauvignon and shiraz. In a sense, you might say it’s still in an investigative, experimental stage. The quantities we take are not inconsequential but we’re still learning about how we might incorporate to benefit these flavours and these different flavours and style we’re getting out of Western Australia.

It’s my view that it would be wise for 15 per cent of JC being sourced from a region sufficiently divorced from where we currently are so that the weather patterns that influence where we are at the moment don’t influence these other areas – as part of an ongoing insurance policy, protecting Jacob’s Creek.

We grow close to 25 per cent of the fruit that goes to Jacob’s Creek. Of the remaining 75 per cent all but five per cent comes from growers with whom we have long term relationships. The remaining five per cent comes from areas, like Western Australia where we are still learning and still developing relationships with growers.

The whole basis of Jacob’s Creek is about reliability. That means we have to know the people we are dealing with and we have to have confidence in them. These long-term relationships guarantee the reliability of Jacob’s Creek. Other than seasonal variation we should get not surprises.

Looking to the future and given the constraints of a limited water supply in south eastern and western Australia, the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range, Queensland, probably has the capability to produce very good fruit – looking forward a decade or two.

Whether or not to include it in Jacob’s Creek will be Bernard Hickin’s decision.

There are a couple of things that are basic and unchangeable about Jacob’s Creek. Jacob’s Creek will always be 100 per cent Australian fruit and Australian wine. It will also always be 100 per cent bottled in Australia, so that it leaves Australia in a bottle with a label on it that guarantees that it is grown in Australia, made by Australians, bottled by Australians and shipped by Australians. That is absolutely key to the integrity of Jacob’s Creek. Being Australian is an integral part of Jacob’s Creek character.

A passion and way of life

For the people who are integral to Jacob’s Creek, it’s their passion, it’s their life, it’s their challenge, it’s their pleasure.

The people who actually make Jacob’s Creek are personally and passionately involved in it. The people who market it are equally passionate but in a slightly different way.

A step back from the makers a there’s group of people within Orlando – it might be viticulturists, vineyard managers, vineyard workers, people working in bottling, or grower liaison officers – who know that decisions they take have a significant bearing on Jacob’s Creek.

Within their own areas these people know what the winemakers want and they know why the want it – because it’s Jacob’s Creek.

Independent grape growers, too, are absolutely integral to Jacob’s Creek. They’re committed through a complex process where each grower has a relationship with a particular winemaker. This winemaker looks after a particular region and he or she will know the grape growers.

There’ll be a grower liaison officer as the commercial contact. And there’ll be a viticulturist. So they’ve got three points of a relationship that’s ongoing throughout the year. They’ll see the winemaker two or three times year; the viticulturist half a dozen times; and the grower liaison officer almost constantly.

And at least once a year those growers will have an opportunity to meet the Chief Executive and to see a marketing presentation giving global and domestic overviews and an update on how Jacob’s Creek and the company are travelling.

Separate to that each grower is invited to visit the winemaker responsible for his fruit and to taste the wine that it ended up in and to compare it to wine made from fruit from other growers.

They will also taste Jacob’s Creek to give them an understanding of what we are trying to achieve stylistically.The aim is to give the growers a feeling about Jacob’s Creek and where they fit into it – and the importance of where they fit into it. This helps them understand how they can contribute to making a better bottle of Jacob’s Creek.

The effect is that they develop a pride in Jacob’s Creek. And if their fruit achieves a higher grading, the effect on the grower is enormous. They’re really chuffed. And they become even more committed.

Marketing and winemaking link

There’s a big link between marketing people and winemaking people because the direction that Jacob’s Creek is going – with the development of new products and with evolution of existing products – is very much the combined role of marketing and wine people. Neither one can act independently.

If through our observations at home or away we feel that changes should be made, we don’t just do it. We would then speak with marketing and say what we think ought to be done and ask if they agreed. It would be unusual for them to disagree, because the respect between marketing and winemaking is excellent. It has to be, because if that ever broke down the whole thing would fail.

The marketing people are quite prepared to accept – not blindly – the opinions being expressed by winemakers about how we rate with our competitors, what we might need to do, what we might think consumers are doing.

And in the same way, the winemakers respect what the marketing people are doing in terms of the evolution of the advertising, the packaging, the promotion of Jacob’s Creek. While we have views about what the label should like and what’s a good promotion and what’s not, at the end of the day there’s a lot of respect.

This is helped a lot by the fact that there’s this very rational guy sitting at the top, Stephen Couche. He’s like the gatekeeper.

Don Lester, the viticulturist behind Jacob’s Creek has 25 years service. He’s now in quality assurance.

Why I like going to work

I don’t think I’ve ever woken up and said, I don’t want to go work. I’ve woken up and said, this is not going to be a great day.

I routinely get up early and aim to be at work by 7 or 7.30am – and I might drop in at a vineyard or Richmond Grove Winery [Another Barossa winery of Jacob’s Creek owner, Pernod Ricard].

People who work at Jacob’s Creek are those that are concerned with getting things right. You could, say, make a blend in five minutes or you could say, look I want to try this, that, this that or the other – so, you could stay there for five hours until you’re satisfied. That’s the Jacob’s Creek approach. You might still end up where you started. But you’ve satisfied yourself that you’ve tried every possibility as to how you can make the blend more appealing. It’s not about being expeditious. The key people are those that keep trying and trying and trying.

Influence of staff passion for wine and food on JC wine style

If you go back to this basic premise of Jacob’s Creek that eight or nine bottles of every ten are drunk with or around food and therefore JC has to be something that works wonderfully well with food or is very supportive of food, then this food link is very important.

One of the reasons we employ Veronica Zarha, who is a stunningly good chef, is because she has a fascination with wine and food matching – especially with historic associations.

She’s, I think, Maltese. She works at the winery and she’s got a couple of kitchens – one at Roland Flat and one at the Heritage Vineyard – where, amongst other things, she fiddles around with local produce.

Veronica works closely with the winemakers. Whoever she reports to doesn’t get much joy out of her, because she completely ignores them.

Her focus is on food and wine, to the extent that she’ll periodically say, please bring me in yet again, I need to be put through a tasting, because I want to remember what it is that you people are saying about wine.

And she will try to come up with common sense (mostly) food that can be used for recipes and what have you with Jacob’s Creek – and try different things, so that we’ve got a series of recipes that are quite simple.

It could be as simple as oysters and riesling; or highly complex, depending on the occasion – so you’ve got the opportunity to say here’s a series of recipes – some simple, some increasingly complex – that work with Jacob’s Creek, and here’s the reason why.

So we get to enjoy her food a lot. She works wherever possible within South Australia. But where she can and because it’s an old property she uses our own produce: we’ve got quince trees, a range of olive varieties planted by the Gramp family years ago, peaches and figs – and then beyond that she uses local produce as much as possible,

So if we’re having fish it’ll be South Australian fish and if we’re having cheese it’ll be South Australian. In fact, we now have Barossa cheese. So, it’s as local as can be, but it has to be practical.

And if, say, the Jacob’s Creek UK team visits the Barossa and says gosh that was good, she’ll send information about the food and wine with them and they’ll distribute it when they arrive home.

While a lot of the food is South Australian, because fish is fish and lamb is lamb, you can adapt the recipes to any part of the world.

Veronica will shortly cook her first Jacob’s Creek all-Australian menu overseas – in Sweden – and hopes to do more of this in the future.

My travel

Over the year’s I’ve kept a travel record and in it I’ve just recorded by 6,500th flight – all of which is related to wine. It’s a combination of domestic travel, light aircraft travel and international travel throughout my winemaking career – including the fifteen odd years that I’ve been winemaking for Jacob’s Creek.

I get to see an awful lot of the world on behalf of Jacob’s Creek – forty different countries to date. And there’s a very real need to visit all the countries that sell Jacob’s Creek to communicate with the people that sell and market it so that they have the same understanding of Jacob’s Creek that we do. The contact needs to be a reasonably routine thing.

My role as the Jacob’s Creek global educator

An important part of my life is in providing an education to the people who market Jacob’s Creek around the world.

Sometimes, not always, it requires an education about wine. It always requires an education about Australia and Australian wine – and then, specifically to shed light on why Jacob’s Creek, within Australia, has its own niche.

In the UK I conduct education sessions for not just for our own people but for the restaurant and retail trades as well.

Unique characteristics of the Australian wine industry

One endearing element of the Australian character is the ability to be frank and open. This shows not just in Australian winemaking but in how winemakers talk about their wines to the press, the trade and the public.

Australian winemakers will talk openly about what they’ve attempted to do with their wines and will equally openly talk about what they see as shortcomings and how they plan to overcome these in future vintages.

The Australian industry has a number of unique strengths.

One of them is cooperative research and development where we pool our resources in cash and generate world class R & D in terms of wine and viticulture.

There are two main reasons for this co-operative approach. If we attempted it individually the resources would be insufficient. And, second, if anyone sells a bad bottle of Australian wine it reflects on all of us.

You want your neighbour to make good wine – not as quite as good as yours, perhaps – but good wine, nevertheless. So this cooperative research guarantees that this information gets out to everybody and, in a sense, is forced upon them.

At a more informal level, winemakers talk to each other. If we have a problem that we haven’t seen, I know we could ring up a counterpart in another company and say, look have you seen this. And if they had, they’d say, yep – and this is how we went about fixing it.

I don’t believe any other winemaking country – except perhaps New Zealand – enjoys this level of cooperation. It’s integral to Australian wine quality.

It’s interesting that the United States and Chile have written to Australia seeking to copy our cooperative research model, something we’ve consciously built to be an enduring part of our winemaking culture.

Its success in Australia comes from a preparedness to make it work. And that springs from our culture. We can explain how it works to our friends in the US and Chile, but that doesn’t mean they have the preparedness or culture to make it work in their environment.

It’s a reflection of Australia. The nature of Australians is such that you can sit down and work together. It is a friendly country. You trust one another. You’re quite prepared to share information with other people because you know you’re not going to be exploited. And when the boot’s on the other foot, you know they will help you.

It comes to a point where it’s every man for himself, when you’re in the market. But until that point you sit down and work together.

This is very much the Australian ethos and it goes back to our very beginnings. If we hadn’t worked together and cooperated, we wouldn’t have survived.

Jacob’s Creek Reserve Range – a consumer perspective

The reason we introduced a Reserve range was to provide somewhere for those people who were Jacob’s Creek drinkers and wanted to move – and particularly outside of Australia where we were Jacob’s Creek and that was it.

So, if you moved on from Jacob’s Creek there wasn’t anywhere to go. In Australia you might know the link between Jacob’s Creek and Orlando. So we needed something to offer those people and the Reserve range fulfilled that role in giving those people something that Jacob’s Creek familiar, but that was Jacob’s Creek at a much higher level.

The second role was to attract those people whose entry level was $15, not $8 – because those people would not consider Jacob’s Creek and here was a way of interesting those people. And perhaps if they liked the Reserve to encourage them, in a sense, to trade down.

And the third bit, which is in a sense the most important bit, was to do something that made a statement about Jacob’s Creek and about building the reputation of Jacob’s Creek – that this brand which everybody likes and respects but knows is good value at $7 to $10 bottle actually has much better credentials. It can make remarkably goodcwine that warrants you paying $15 or thereabouts.

In terms of the winemaking philosophy each of the wines in the Reserve range had to be very, very faithful to the Jacob’s Creek style. So it wasn’t a matter of making a better chardonnay, or a better riesling or a better shiraz. It was very much a matter of making a better Jacob’s Creek Chardonnay or a better Jacob’s Creek Shiraz.

So it had to fit the Jacob’s Creek mould and it had to be something that whoever bought it would know immediately that they’d got something that was worth more than they paid for it.

You got something that was better than you were anticipating – and for two reasons. One, somebody buying for the first time a better bottle of Jacob’s Creek is going to be suspicious. They know where Jacob’s Creek is, so you’re buying it on the basis of well, if I’m disappointed, then it won’t be a surprise.

So you’ve got to cater for that sort of cynicism by having something that guarantees when that person gets to it they’ll say, Jesus Christ, I was wrong. That’s a bloody good wine.

And for those people who are not cynical, the same sort of thing, I’ve got myself a very good bottle of wine for $14 or $15. I’m delighted with what I’ve got.

That was the message behind it.

Comparing old world wine styles to new world styles

When it come to Australian wines it’s words like generosity, flavour, softness and roundness. Australian wines are not harsh, bitter, thin and they tend not to be acidic. There’s more generosity to them in terms of colour, flavour, palate. Probably people in the sort of markets into which we sell nowadays drink more wine socially than would have been the traditional European thing where it was perhaps more tied around meals.

I think a lot of wine consumed in Australia and in the UK is just a drink. And a lot of European styles are quite difficult in that situation. Most are fairly astringent reds. And the whites tend to be much leaner and more austere than Australian white wines which are generous in the sense that they’ve got plenty of alcohol, the fruit’s ripe, so there aren’t any green or weedy flavours. The wines are well made so you tend not to get oxidised sulphur flavours that come through in similarly priced European wines.

You’re getting well made wines because the fruit’s good, therefore there are no extraneous flavours being introduced into the wine. You’ve got nice, ripe flavours which are soft and round and generous – it’s got nothing to do with sugar – it’s about ripe fruit flavours. Just having a glass of wine, you can understand the enormous appeal of having a glass of Australian chardonnay.

It’s just a very easy thing to drink. You don’t have to think about it. It’s got flavour and softness and, importantly, there are no turn offs. There isn’t a green acidity at the end of it. There aren’t some funny flavours that you’re not sure where they came from.

And, furthermore, the next bottle you buy is going to be very similar, because unlike buying European wine, where you buy chardonnay X today and chardonnay Y tomorrow – you don’t have this opportunity to buy by brand, and a lot of old world winemakers don’t have the same philosophy about reliability that we have.

I don’t know whether it’s because they consciously try to bring out the expressions of the vintage – “this is the way it was, this is what you get”. I’m sure it’s not, unless you’re at the top end. But to some degree that’s the philosophy, rather than trying to produce something which is reliable so that the consumer from year to year’s going to develop some loyalty because he knows pretty much what he’s going to get.

And it’s not natural seasonal variation. It’s a lack of dedication. There’s no reason in the world why five, six, seven-pound European wine has to be as bad as it is.

What is special about the Barossa

It’s typifies what Australia is all about. And what is interesting from a UK point of view is that there are little townships in the Barossa – we regard as quite big – but the biggest one has 2500 people, and the smallest one is three or four hundred. In other words we’re talking about something that is quite small and cute.

It’s a spectacular place. We have cool winters around fifteen degrees. We have warm summers around 30 to 40 degrees. There’s open space. There are places in the Barossa where you can sit all day and not see a motor car.

You can sit in parts of Jacob’s Creek and you might glimpse parts of a few odd buildings in the distance – so it’s still very rural.

The most appealing time to me is summer, when the hills have gone brown. I reckon the brown Barossa hills when the grass has dried off provide a contrast to the green vines in the valley that’s just absolutely fantastic.

I know you’re meant to think the autumn is the best when the vines leaves change – and it is wonderful. But just love these lovely brown hills.

When I’m overseas and somebody says what is your favourite colour, I invariably say brown. They look at me and I say it’s because brown reminds me of home – and

it’s not brown awful, it’s brown lovely. You get these wonderful brown colours.

The Barossa is a wonderful place to live and work in because it’s between what is station country 60 kilometres to the north at Burra where it’s grazing country and it doesn’t rain and Adelaide, 80 kilometres to the south.

You’re in between and you have the best of both. It’s really is very much a rural lifestyle. In developing behind Jacob’s Creek we have gone to great pains to bring Jacob’s Creek itself back to the way it would have looked when William Jacob was still alive and Johann Gramp established his vineyard.

Over the intervening 150 years there had been the introduction of all types of new species of European trees and flowers and what have you, which have crowded out the native vegetation.

So in recent years we’ve taken Jacob’s Creek back to where it was. It’s just wonderful to go down and sit there – whether there’s water or not in the creek (and for six months there isn’t) and look at trees that would’ve been alive and growing when William Jacob and Johann Gramp arrived there 160 years ago. Those trees are still there.

It’s now pretty much the way it would have looked and would have sounded – not the same Kookaburras and not the same Magpies, because it’s a few generations on, but the bird life is still the same.

You can actually say, in many respects, nothing has changed in 150 years. Sure, if you listen, you might hear a truck on the road or a tractor in the vineyard, but so much is identical. We still grow vines – the same varieties from the same cultivars. The soil’s the same. The climate’s the same. The hills still look the same. And Jacob’s Creek itself still looks as it did. It’s wonderful that so much in 150 years hasn’t changed.

Copyright © Chris Shanahan 2006 and 2020

Transcript of an interview with Phil Laffer, Canberra, 16 March 2006