For a long time my wife Jill and I had wanted to visit Western Australia’s remote Kimberley region – and in July this year we did.

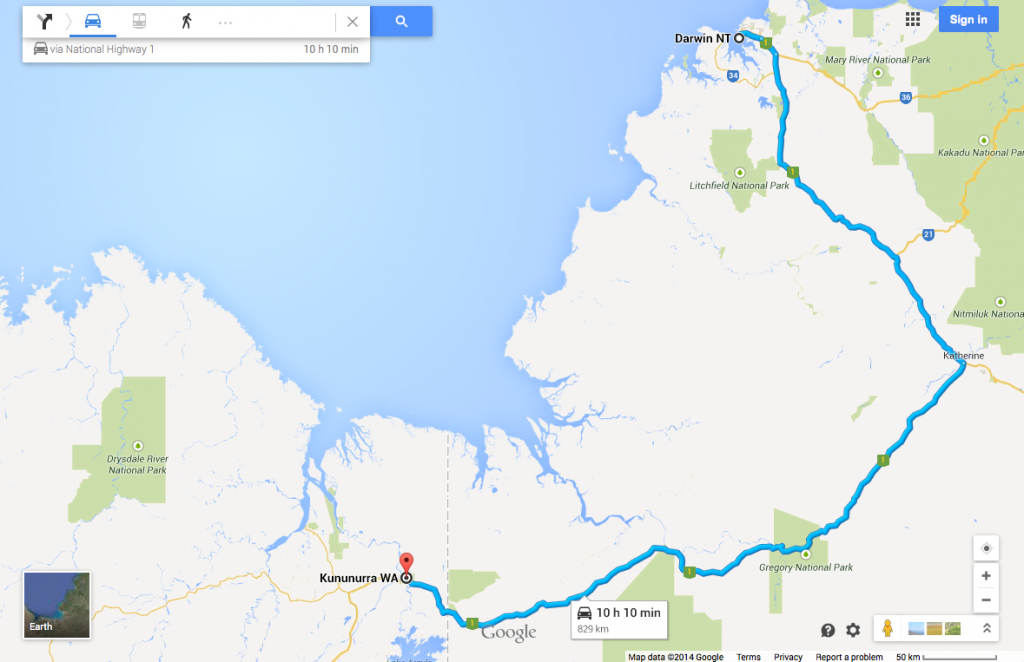

We flew out of a frosty Canberra morning and arrived in Darwin’s friendly dry-season heat at lunchtime. We collected our Apollo four-wheel-drive camper, stocked up on food and wine at the nearest Woolies store, then camped the night in a Stuart Highway trailer park ready to begin our journey south to Katherine, then west to Kununurra, Western Australia, the following morning.

Having enjoyed the independence of a Northern Territory trip in a similar vehicle two years ago, we had opted to drive and camp through the Kimberley, too. We initially held some misgivings about the Gibb River Road and the infamous Kalumburu and Mitchell Falls roads.

But our misgivings faded after talking to a workmate David Evans-Smith. He’d driven and camped through the area with his family a few years earlier. He assured me even the rough Mitchell Falls road, “isn’t technically difficult”. And so it proved – though the road takes a mighty toll on vehicles, as we found out first hand.

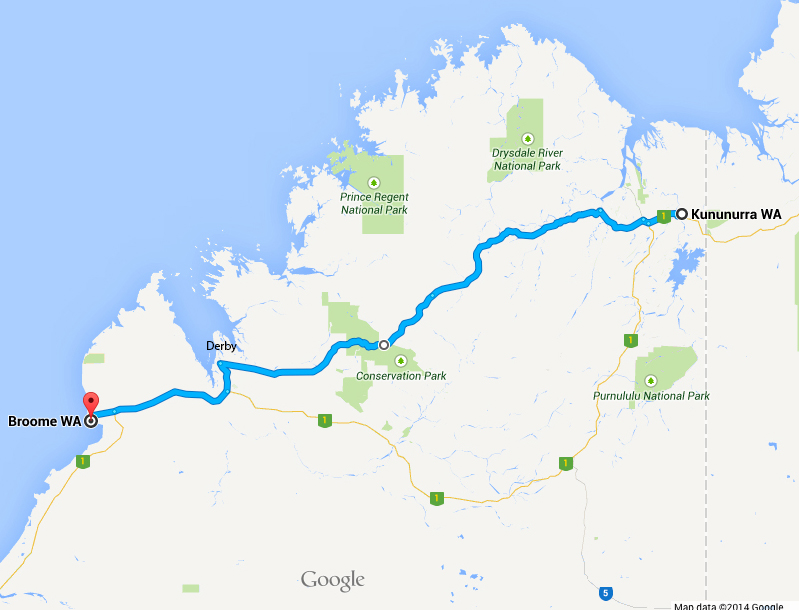

A driving tour of the Kimberley normally takes in the roughly 1,000km from Broome in the west, via Derby, to Kununurra in the east. Two roads traverse the region east-west: the sealed Great Northern Hightway (Highway 1) and, to its north, the mainly dirt Gibb River Road.

The sealed Great Northern Highway (Highway 1) trends east and slightly south from Broome before cutting north to Wyndham, with an east-bound turn-off to the Victoria Highway (now Highway 1) to Kununurra. The total distance is 1043 kilometres.

The Gibb River Road (to the north of the Great Northern Highway) begins at Derby (220km west of Broome, sealed road) and joins the Victoria Highway 45km west of Kununurra. The total Broome-Kununurra distance by this route is 917km, but about 550km of it is dirt. It’s a stony but fairly good road, with bone-shaking corrugations in sections (depending on where the grader happens to be).

A comprehensive four-wheel-drive road tour of the Kimberley logically begins and ends in Broome – driving along the Gibb River Road in one direction and the Great Northern Highway in the other.

The Gibb River Road provides access to spectacular gorges along the entire route as well as to the Mitchell Falls and Kulumburu, on the coast. The Great Northern Highway, on the other hand, passes the access road to one of the Kimberley’s most spectacular attractions, the Bungle Bungle Ranges, part of Purnululu National Park.

We originally planned to explore the Kimberley on this circuit. However, we changed our minds when Apollo offered a substantially lower hire rate for picking up our vehicle in Darwin and leaving it in Broome.

The 900km Darwin-Kununurra drive is actually 100km shorter than the Broome-Kununurra drive. However, coming into the Kimberley from the Kununurra end, meant a return 700-km drive from Kununurra to the Bungles and back again before we could head west on the Gibb River Road.

And what a lovely, scenic drive it was – uncrowded and easy on the 250km sealed Great Northern Highway road south to the Bungles turn-off, then rough as guts on the 53km access road. For two nights we enjoyed the serenity of Walardi campground in the south of the park.

During the days we drove to the walks – Piccaninny Creek and Cathedral Gorge in the south and Echidna Chasm in the north; and enjoyed a chopper ride over the unique sandstone domes of the south. We needed another night and day, really, but we cut and ran back to Kununurra. The 700km Kununurra-Bungles-Kununurra drive included about 200km of dirt driving to access the park and drive around within it.

There’s plenty to see around Kununurra, the centre of the massive Ord River scheme. We took time to boat the 50km from the town’s diversion dam up Lake Kununurra to the wall of the Argyle Dam, holding back about 1000 square kilometres of water.

Water from the lake drives a hydro electricity plant and, with Lake Kununurra, irrigates about 150 square kilometres of farmland on the Ord flood plains. These are awesome to view. And we found one farmer, Spike Dessert, distilling outstanding rum and whiskey from the local sugar cane and corn (see Kimberley bookends below).

From Kununurra, we headed west to the Gibb River Road. By this time we’d already driven about 300km of dirt, crossed many streams and learned to hate unrelenting corrugations, like those of the Bungles’ access road.

Ever-changing landscapes, dust and corrugations lay ahead and by now we felt some excitement about the coming climb up to the Mitchell Falls. Because of its remoteness and ability to break cars, the falls remain forbidden territory for many hire vehicles, which now cross the Gibb River Road in good numbers.

Before we left Canberra we sought Apollo’s permission to drive to the falls, and they obliged. However, we stayed overnight at El Questro station, the nearest gorge county to Kununurra. Here we explored Emma Gorge and relaxed in the Zebedee Hot Springs, before fleeing the large crowds.

After a peaceful overnight at Ellenbrae Station the following day, we headed further west before turning north, about 300km from Kununurra, onto the Kulumburu Road for the 250km drive up to Mitchell Falls.

We rested, showered, enjoyed a cold one and camped overnight at the very hospitable Drysdale Station, about 60km north of the Gibb River Road. Early next morning we bounced north on the Kalumburu Road’s endless corrugations. About 105km later we turned left onto the Mitchell Plateau Road. After about eight, narrow, rocky kilometres (second gear territory), we crossed the pristine King Edward River and followed a wider but terribly corrugated road through the marvellous livistona palms.

About 40km short of the falls, we offered help to a carload of American scientists. They waved us on. But 200 metres later our car died and the Americans came to our aid. A bracket securing our battery had broken free from one of its moorings to fuse itself onto the positive terminal. The short circuit drained the battery, fatally as it turned out.

A few metres of nylon rope re-anchored the battery, thanks to the American scientists. Six people pushed the vehicle to a successful clutch start, and a tense hour and a half drive to the campground followed, with a near-dead battery. Warning lights flared intermittently on the dash, but thankfully these turned out to be a false – a result of the battery damage.

Despite the best efforts over the next few days of park ranger, John Hayward, the battery not only failed to recharge, but exploded, spewing acid, when we attached jumper leads. However, Hayward manufactured a new battery support bracket from a tent peg, which we stowed optimistically for the time we’d find a new battery.

We ditched the dead battery and after creating a circuit without it, unsuccessfully attempted a clutch start sans battery.

By this time, Nathan, a RAAF aeronautic electrician camped nearby, had joined the rescue effort. He established a trickle of electricity from the fridge battery to the Toyota’s computer, just enough to switch on the dash lights. The diesel clutch started instantly at the next effort, allowing us to drive the 190km back to Drysdale station, with no battery and hoping we wouldn’t stall on the way. We didn’t.

Our three nights at Mitchell Falls proved a highlight as we walked all over this beautiful, remote region. With other campers, we attended John Hayward’s night time presentation on the area during the wet season, ancient rock-art sites in the vicinity and his notable work with academics from the universities of New England and Wollongong.

Hayward discovers new sites during his wet-season explorations, then works with the university teams and local Indigenous people on excavations and attempts to determine the age of rock art.

After our four and half hour, battery-free drive from the falls, we installed a new battery and rested overnight at Drysdale Station. Next day we moved on to the beautiful, serene campground of Charnley River Station, 42km north of the Gibb. We explored the property’s gorges for two days and listened to the dingo chorus at night.

We moved westward again, then headed south from the Gibb River Road to Tunnel Creek – scrambling through a 750-metre, watery tunnel through a craggy limestone reef, dating from the Devonian period. We spent our last night on the Gibb River road at Windjana Gorge, another limestone formation of the Devonian era, a short but corrugated drive north of Tunnel Creek.

From there we headed to Broome, via Derby, taking in the local sights, riding a hovercraft to the famed dinosaur footprints and visiting brewer Marcus Muller at Matso’s brewery (see inset).

We spent just 24 days on the road from Darwin to Broome, travelling about 4,000 kilometres – about 2,000 of it on dirt. Our sturdy Toyota Hilux, or Hilux Hilton, proved to be the ultimate downsizing exercise – moving from a five-bedroom Canberra home to a mobile bedsitter.

For three weeks we slept comfortably and ate and drank well from a 32-litre fridge – where two 500-litre behemoths seem often not big enough for our extended family.

We met so many people all ages from all over the world. But we particularly enjoyed our encounters with young Australian families, travelling the country and taking their kids out of school for three, six and even nine months.

Our only regret: not allowing more time. There was so much we didn’t see on the Gibb River Road. Nor did we travel north from Broome to Cape Leveque, as we’d originally hoped, or south to Fitzroy Crossing, or Wolf Creek crater.

We concluded that any able bodied person can do this trip. You need a four-wheel drive, principally for its high clearance and sturdy suspension. But you don’t need any particular driving experience. The car does all the hard work. However, if you do venture to more remote places, a severe breakdown could become extremely time consuming and very expense.

Our travel guides were few but excellent: Birgit Bradtke’s comprehensive Destination Kimberley and Hema Maps’ The Kimberley Atlas and Guide. Both are available online.

Kimberley bookends

We book-ended our east-to-west Kimberley drive with visits to Kununurra distillery, the Hoochery, and Broome landmark, Matson’s Brewery.

Hoochery owner, Spike Dessert, moved to the Ord River area from the USA in 1972, bought land in 1985 and cultivated seed crops from 1986. Thirteen years later, inspired by South Australian cellar door winery operations, Dessert established a distillery and cellar door facility. The complex, which also serves food and caters for functions, soon became one of Kununurra’s major tourist attractions.

“I liked the cellar door concept”, says Dessert, “but obviously you couldn’t make wine at Kununurra”. Instead, he built his own still, based on research of USA hill distillers, to make rum and whiskey from local sugar cane and corn.

About 1,000 kilometres to the west, in Broome, Martin and Kim Pierson-Jones’s Matso’s Brewery, offers ocean views, decent food and beers made for the tropics. Matso’s hugely popular ginger beer (in fact, a blend of wine, ginger essence and water) joins a quirky drinks list that includes mango, chilli and lychee beers. However, brewer Marcus Muller makes several delicious, traditional lagers and ales in addition to these sweeter tropical thirst quenchers.

Our vehicle

You can tour the Kimberley in complete luxury, flying in from Broome or Kununurra or from a cruise ship on the coast. Accommodation ranges from luxury lodges to basic bush camping, sometimes with showers, always with composting toilets. Where there are no showers, croc-free fresh-water swimming holes do the job.

We took the fly-in, self-drive approach and selected our Apollo Adventure Camper after considering the many other four-wheel drive options. We simply liked what it offered for two people: a sturdy turbo-diesel Toyota Hilux ute with a camping unit on the back.

The camper, with its pop-top, comprised a comfy, large double bed, a 32-litre fridge with its own battery, crockery, cutlery, sink, 60-litre water storage and ample cupboard space for clothing and food storage.

A panel with a two-burner gas cooker folded down from the outside. This and a couple of outdoor chairs and a fold-up table, allowed us to cook and eat outside – which is extremely pleasant during the tropical dry season. The inside we used only for storage, changing, sleeping and night time reading.

Copyright © Chris Shanahan 2014

First published 14 September 2014 in the Canberra Times

Mitchell Falls photos:

– dry season © copyright David Evans-Smith

– wet season © copyright John Hayward.