On June 29 in Moscow, Penfolds told the world the best seal for wine is glass. They didn’t say it in so many words. But that’s the message dramatically delivered in twelve $168,000 glass ampoules of Penfolds Kalimna Block 42 Cabernet Sauvignon 2004. Yes, just 12 for the whole world. And the problem for Penfolds will be allocating them, not selling them.

On June 29 in Moscow, Penfolds told the world the best seal for wine is glass. They didn’t say it in so many words. But that’s the message dramatically delivered in twelve $168,000 glass ampoules of Penfolds Kalimna Block 42 Cabernet Sauvignon 2004. Yes, just 12 for the whole world. And the problem for Penfolds will be allocating them, not selling them.

The price tag, quality of product, originality of the idea and launch at Moscow’s Pushkin Restaurant (with a run of legendary old Penfolds reds lavished on the guests) ignited huge global publicity.

Behind the cleverly executed campaign, lies years of thinking by winemaker Peter Gago about the best way to seal wine intended for decades or even centuries of cellaring.

By the 2004 vintage Penfolds had adopted screw caps for all its reds except Grange. And in a 2007 interview, Gago told me why not, “‘With Grange we’re talking about people cellaring it for thirty to fifty years. We’ve had trials for ten years, but we’ve got our fingers crossed that these wines will still be good in four or five decades. It’s the integrity of the seal, not ageing that’s of concern”.

He explained that while we knew screw cap seals kept white wines perfectly for thirty years, the chemistry of red wine is different and we simply don’t know for certain whether the seal will last.

He recalled working with well-known sparkling-wine maker, Ed Carr, at the company’s sparkling cellars. They observed how crown seals on sparkling red wines often deteriorated where those for sparkling whites didn’t.

Gago believed a glass-to-glass seal presented the best solution as there’d be nothing to corrode – no perishable material like cork, the tin or polymer coated material in screw caps or the silicon o-ring of the glass Vino-Lok.

Indeed, Penfolds had already engaged an engineer to develop a prototype – a glass disc held in place with a spring-loaded clamp.

Two years later Gago told me they’d developed a second prototype, “a pseudo screw cap” holding a glass disc in place, and had tested both on the 2006 vintage Grange. He said he’d like to take it to the next level, but that would require money – an unlikely outcome at the time as parent company Foster’s struggled with its wine division.

During both the 2007 and 2009 interviews, Gago discussed the concept of a “time capsule” – a wine sealed in a continuum of glass, capable of cellaring for centuries. That’s the dream that became a reality in the recently released ampoule.

Gago calls the ampoule project and the earlier glass-to-glass trials “parallel pursuits” – separate but interrelated. He hopes that success of the radical new ampoule might spark enthusiasm for glass seals within in the company. All it needs now is money, and imagination.

It presents a golden opportunity for Penfolds new managing director, Gary Burnand, to make his mark on the company and, indeed, on the entire wine world. The ampoule gave us the first ever perfectly-sealed wine. By supporting Gago’s glass-to-glass concept he could usher in the most radical technological change since the invention of the glass bottle.

Kalimna vineyard, Block 42

In the nineteenth century, this northern Barossa site provided firewood for D.J. Fowler and company. In the 1880s, precise date unknown, George Fowler planted and named the Kalimna vineyard. Penfolds bought it in 1945 and its fruit subsequently starred in many of the company’s greatest reds – including blended wines like Grange and several notable cabernets sourced only from Block 42. These include Kalimna Cabernet Sauvignon 1948, Grange Cabernet Sauvignon 1953 and the first Bin 707 Cabernet Sauvignon (1964).

Winemaker Peter Gago rates Grange cabernet 1953 slightly ahead of Grange Hermitage 1953, in his view the best Grange ever made.

Gago says the low-yielding Block 42 produces extraordinary wine in some vintages. In the most recent outstanding vintages, 1996 and 2004, Penfolds released cabernet under the Kalimna Block 42 name. The wines tend to fetch $500–$600. The ampoules contain the 2004 vintage. Penfolds believes the venerable old vines on Block 42 to be the oldest continuously producing cabernet sauvignon in the world.

What you get for $168,000

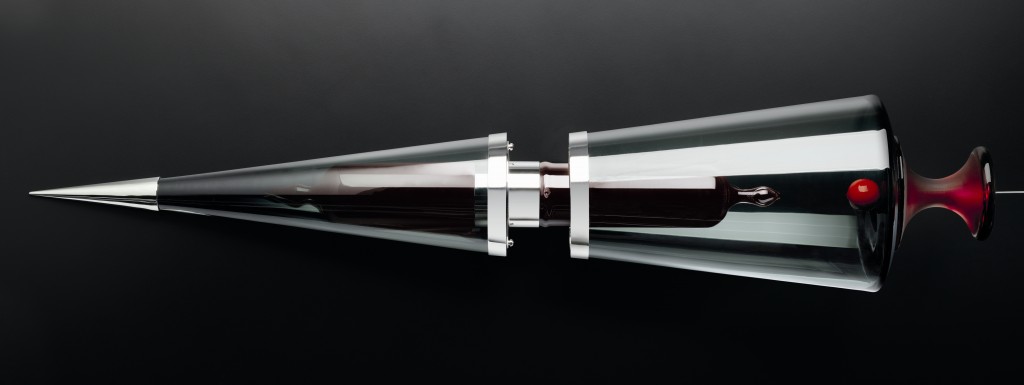

- 750ml of Penfolds Kalimna Block 42 Cabernet 2004 in a glass ampoule, designed and hand-blown by glass artist Nick Mount.

- A grey and ruby coloured glass plumb-bob, designed and hand-blown by Nick Mount. The plumb-bob suspends the ampoule in its Jarrah cabinet.

- Jarrah cabinet designed and made by furniture craftsman, Hendrik Foster.

- Precious metal details designed and made by Hendrik Forster.

- A Penfolds winemaker will travel anywhere in the world to open the wine using one of two purpose made tungsten tipped devices to cut and snap the glass tip of the ampoule.

Penfolds produced 12 sets of ampoules for the world market. One remains in the company’s museum cellar at Magill, Adelaide. One is to appear at an event in Singapore next year, but exactly how isn’t clear. The remaining ten are up for grabs as I write. Penfolds also produced and is retaining in its Magill cellar an additional stand-alone ampoule of Kalimna Block 42 2004, without the plumb-bob, precious metal trappings or timber case.

Penfolds Managing Director, Gary Burnand, says retailers and private collectors around the world want the ampoules. Allocating them could take all the diplomacy in the world.

Copyright © Chris Shanahan 2012

First published 18 July 2012 in The Canberra Times